#Dr Carter G Woodson

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Today In History

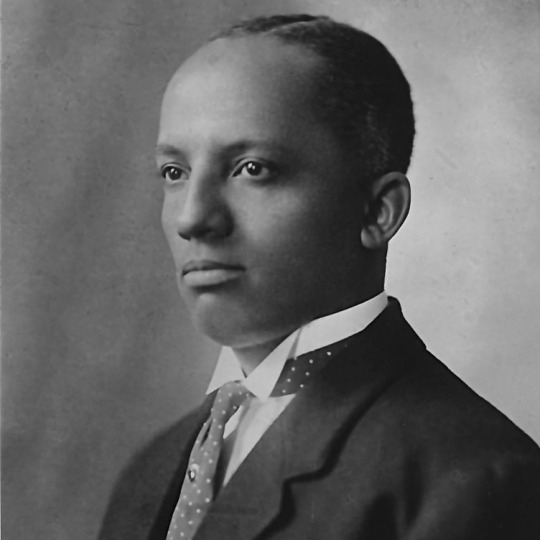

Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson, was born in New Canton, VA, on this date December 19, 1875. Woodson had worked as a sharecropper, miner and various other jobs during his childhood to help support his large family. Though he entered high school late, he made up for lost time, graduating in less than two years. After attending Berea College in Kentucky, Woodson worked in the Philippines as an education superintendent for the U.S. government. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Chicago before entering Harvard. In 1912, three years before founding the ASNLH (Association for the Study of Negro Life and History).

Dr. Carter G. Woodson became the second African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University after W.E.B. Du Bois.

Woodson believed that young African Americans in the early 20th century were not being taught enough of their own heritage, and the achievements of their ancestors. In 1921 Woodson started his own publication the Associated Publishers Press and housed it at his row house on Ninth Street in Washington D.C. He then turned to his fraternity, Omega Psi Phi, who helped create Negro History and Literature Week in 1924.

In February 1926, Woodson sent out a press release announcing the first Negro History Week. As early as the 1940s, efforts began to expand the week of public celebration of African American heritage and achievements into a longer event. In 1976, on the 50th anniversary of the first Negro History Week, the Association officially made the shift to Black History Month.

Woodson dedicated his career to the field of African American history and lobbied extensively to establish Black History Month as a nationwide institution. He wrote many historical works, including the 1933 book The Mis-Education of the Negro.

We honor Dr. Carter G. Woodson legacy through CARTER™️ Magazine, extending his vision for making African American history available for everyone 365 days a year.

CARTER™️ Magazine

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#dr carter g woodson#carter g woodson

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

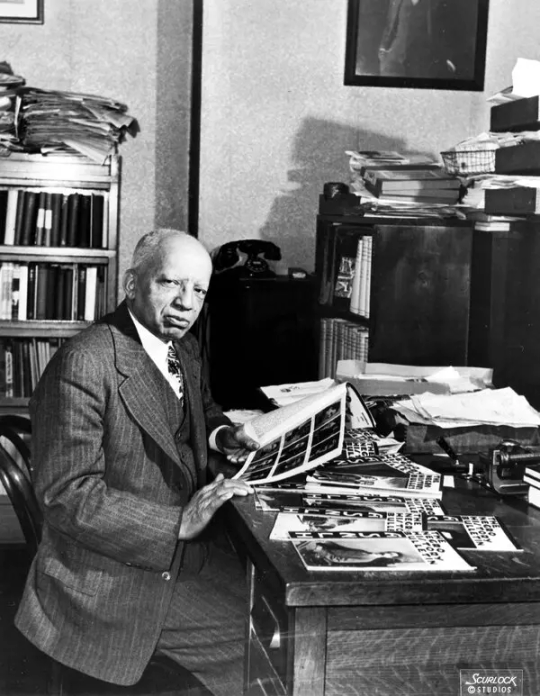

In 1922, Carter G. Woodson, known as “the father of Black history,” bought the home at 1538 Ninth Street NW for $8,000.Credit...Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

In 1922, Carter G. Woodson, known as “the father of Black history,” bought the home at 1538 Ninth Street NW for $8,000. The home served as the headquarters for the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (which is now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, or A.S.A.L.H.).

It was where he ran the Associated Publishers, the publishing house focused on African American culture and history at a time when many other publishers wouldn’t accept works on the topic. It’s where The Journal of Negro History and The Negro History Bulletin were based, and it’s where he initiated the first Negro History Week — the precursor to Black History Month — in 1926.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” Dr. Woodson famously wrote.

The site, owned by the National Park Service, is being restored and will likely be open to visitors starting this fall, a spokesperson for the Park Service said.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” Dr. Woodson famously wrote.Credit...Kenny Holston/The New York Times

Though Dr. Woodson was the kind of neighbor who doted on children playing on the street and his stoop, even as other adults told them to behave, 1538 Ninth Street NW was more about his life’s work than serving as a traditional residence. It became known as Dr. Woodson’s “office home,” as Willie Leanna Miles, who was a managing director of the Associated Publishers, put it in her 1991 article “Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson as I Recall Him, 1943-1950.” The article was published in The Journal of Negro History, which was founded by Dr. Woodson and is still running as The Journal of African American History today.

#The Home of Carter G. Woodson#the Man Behind Black History Month#Dr Carter G Woodson#Black History Month#BHM24#2024#1538 Ninth Street NW DC#The Journal of Negro History#Association for the Study of African American Life and History#A.S.A.L.H#The Negro History Bulletin#Black Historians#Father of Black History Month

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carter G. Woodson: Pioneering Black History and Empowering Generations

Introduction:Carter G. Woodson, often hailed as the “Father of Black History” was a trailblazing African American historian, author, and journalist. His tireless efforts and significant contributions have forever changed the landscape of black history, education, and racial equality. This blog explores the life, works, and enduring legacy of Carter G. Woodson. Early Life and Education: Carter…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

The History of Black History Month and Why Dr. Carter G. Woodson is Known as "The Father of Black History"

Born in 1875 in Virginia to formerly enslaved parents who were never taught to read and write, Carter G. Woodson often had to forgo school for farm or mining work to make ends meet, but was encouraged to learn independently and eventually earned advanced degrees from the University of Chicago and Harvard. It was at these lauded institutions of higher education where Dr. Woodson began to realize…

#"Journal of Negro History"#Black History Month#Dorothy Height#Dr. Carter G. Woodson#Jesse E. Moreland#Jesse Jackson#Negro History Week#President Gerald Ford#Vernon Jordan

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

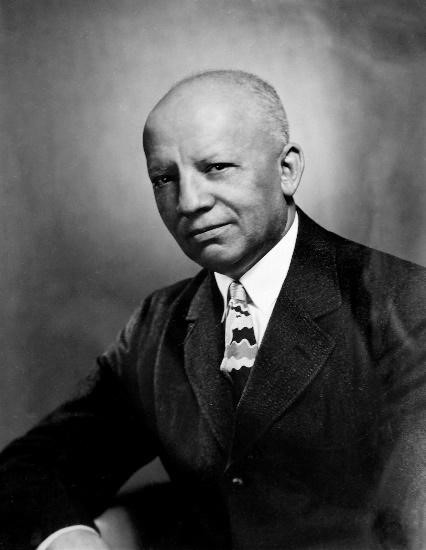

Carter G. Woodson, 1947. Prints and Photographs Division. Library of Congress

The Father of Black History

Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), “the father of Black History,” believed that the only way to achieve racial equality was through the study and elevation of Black excellence. Woodson’s beliefs were not new or unique. Like many who came before him, Woodson believed that education would show the world that African Americans helped build, shape, and bring prosperity to the United States.

Carter Godwin Woodson was born in Virginia, the son of formerly enslaved parents. He spent his life pursuing education and was primarily self-taught in his early years. In 1912 he received a doctorate in history from Harvard University, the second African American, after sociologist and activist W. E. B. Du Bois, to earn this distinction. He went on to work as a school educator and administrator, journalist, and historian. Seeing the effects of white supremacist Jim Crow segregation laws in the South and the devastating toll that the lynching of Black people was taking on the country, Woodson searched for a way to both elevate his community and make white Americans recognize the contributions of African Americans to society.

Education, Abolition, and the Racial Divide

Learning in the face of opposition is a theme that exists throughout African American history. For nearly 250 years in early America, every colony (and then, every state) prohibited or restricted Black education. Although slavery was illegal in New England by the early nineteenth century, education was no easier to obtain for those who were said to be free. A common misconception is that free Black Northerners were safe from enslavement and lived with the same advantages as their white neighbors. However, freedom in New England was tenuous, as glaring economic and social inequalities were a daily part of living. The existence of slavery in the Southern states was a constant threat to free Black Northerners; they could be kidnapped under the guise of fugitive slave laws and sold into bondage in the South. This unstable existence pushed free Black people to search for a way to not only end slavery but to see themselves and be treated as equal citizens. That aim forged the inextricable link between education and abolition.

In his 1933 book The Mis-Education of the Negro, Woodson wrote, “The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worthwhile, depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other people.” His view is apparent in the efforts made in the 1840s on the Massachusetts island of Nantucket. Education petitions pointed out that segregated schools were both injurious to students and an insult to the African American community. They went as far as to equate the situation with being in a South Carolina jail. This comparison drew parallels between Southern slavery and Northern racial prejudice, criticizing Massachusetts and exposing the hypocrisy of the North.

In 1839, seventeen-year-old Eunice Ross of Nantucket was seeking a high school to attend. Like so many other schools designated for the free Black community, Nantucket’s did not provide high school classes, nor did it receive funding equal to its white counterparts. Public school segregation became a major debate, with those in favor of segregation accusing abolitionists of “race mixing” and calling African Americans inferior. Abolitionists fought back, stating the need for equal education and the issues that resulted from segregating students. Despite passing the high school entrance exam and being one of the most qualified who took it, Ross was denied entry because of the color of her skin. Nantucket’s African American community rallied around Ross. There is no record of Ross ever attending the high school but in 1847, all Nantucket public schools began admitting African American students.

The Birth of Black History Month

Woodson’s desire to bring African American history and American history together would lead to the founding of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1916. Woodson was one of a few historians who brought light to the struggle of African Americans in the North and their fight for education. He noted that by 1850, there were 2,038 free Blacks in Boston with approximately 1,500 enrolled in schools. Woodson launched Negro History Week in February 1926, selecting the period that contained the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12) and Frederick Douglass (February 14). In 1970, Black educators and students at Kent State University in Ohio extended the week to a month-long commemoration. Black History Month was adopted nationwide in 1976 during the celebration of the U.S. bicentennial. Recognition has since expanded to Canada and the British Isles.

Black History Month would not only educate whites but also remind African Americans about their long and arduous journey. A journey filled with struggle and determination. A testimony to those like Eunice Ross who fought hard to remind the country of their humanity and their right to equal citizenship. Woodson believed that at some point, Black History Month would no longer be needed. As February draws to a close, it is obvious that it is needed more than ever. Black History Month serves as a reminder to respect, protect, and honor Black lives and to tell the stories that are often dismissed, overlooked, and forgotten. It is in the stories of these pioneers that we can find the strength to continue to move forward and, one day, fully achieve Woodson’s dream.

See more ways to engage with the stories of Black New Englanders, past and present.

Erica Ciallela, a volunteer at Historic New England’s Study Center, holds a master of fine arts degree in history and a master of library information and science. She also volunteers at the Prudence Crandall Museum in Canterbury, Connecticut. The museum was the site of the Canterbury Female Boarding School, where in 1833-1834 town residents violently opposed Crandall’s efforts to educate Black students.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH ❤️🖤💚💛

.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Currently at Carter G. Woodson Museum is Touch in the Spirit of Love, an exhibition of work by professor and artist Dr. Gary L. Lemons.

From the artist about his work (via the museum's website)-

“I am a Black abstract painter. Conceptually, my paintings are rooted in Africentric colors and patterns. I believe art should inspire all people to connect to the liberating power of communal love. Touch in the Spirit of Love is a series of paintings that graphically illustrate the value of love for all humanity. In an imaginary, spiritually enriched context—this series calls all people together to see each other reaching out to one another through the touching of their hands. The hands in my paintings connect people together to express hope for the life-saving power of love committed to community-building. As envisioned by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., hope for a “beloved community” can be realized when people actively join together to show love for social justice. Overall, the paintings in this series visually challenge people to see the need for loving wholeness in mind, body, heart, and soul. Hands of different colors touching each other in this painting series artistically demonstrate the power of love rooted in freedom for all people who have been historically oppressed.”

#carter g. woodson museum#dr. gary l. lemons#st. pete art shows#mixed media#painting#art shows#florida art shows#st. pete museums

0 notes

Text

Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950),

“The father of Black History”

.

Black History Month is an annual observance originating in the United States, where it is also known as African-American History Month. It has received official recognition from governments in the United States and Canada, and more recently has been observed in Ireland and the United Kingdom. It began as a way of remembering important people and events in the history of the African diaspora. It is celebrated in February in the United States and Canada, while in Ireland and the United Kingdom it is observed in October.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

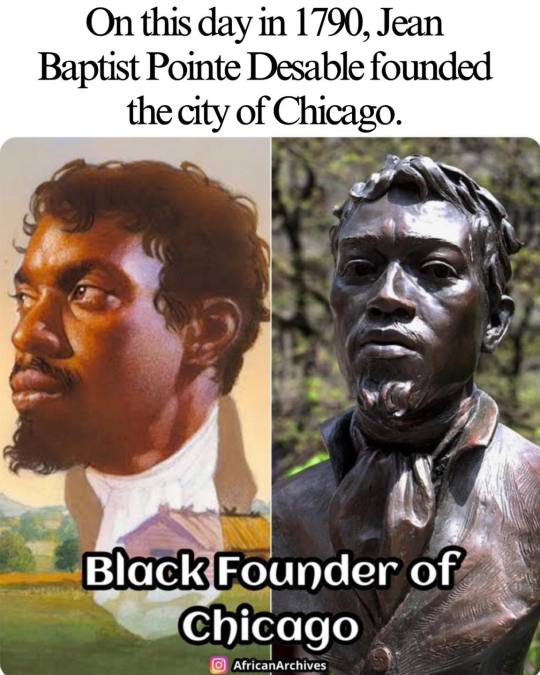

Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable was born in Saint-Domingue, Haiti (French colony) during the Haitian Revolution. At some point he settled in the part of North America that is now known as the city of Chicago and was described in historical documents as "a handsome negro" He married a Native American woman, Kitiwaha, and they had two children. In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, he was arrested by the British on suspicion of being an American Patriot sympathizer. In the early 1780s he worked for the British lieutenant-governor of Michilimackinac on an estate at what is now the city of St. Clair, Michigan north of Detroit. In the late 1700's, Jean-Baptiste was the first person to establish an extensive and prosperous trading settlement in what would become the city of Chicago. Historic documents confirm that his property was right at the mouth of the Chicago River. Many people, however, believe that John Kinzie (a white trader) and his family were the first to settle in the area that is now known as Chicago, and it is true that the Kinzie family were Chicago's first "permanent" European settlers. But the truth is that the Kinzie family purchased their property from a French trader who had purchased it from Jean-Baptiste. He died in August 1818, and because he was a Black man, many people tried to white wash the story of Chicago's founding. But in 1912, after the Great Migration, a plaque commemorating Jean-Baptiste appeared in downtown Chicago on the site of his former home. Later in 1913, a white historian named Dr. Milo Milton Quaife also recognized Jean-Baptiste as the founder of Chicago. And as the years went by, more and more Black notables such as Carter G. Woodson and Langston Hughes began to include Jean-Baptiste in their writings as "the brownskin pioneer who founded the Windy City." In 2009, a bronze bust of Jean-Baptiste was designed and placed in Pioneer Square in Chicago along the Magnificent Mile. There is also a popular museum in Chicago named after him called the DuSable Museum of African American History.

x

#Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable#Haitian Revolution#Chicago history#founder of Chicago#black history#Native American wife#Kitiwaha#American Revolutionary War#British arrest#Michilimackinac#St. Clair Michigan#trading settlement#Chicago River#John Kinzie#European settlers#Great Migration#Carter G. Woodson#Langston Hughes#Windy City#bronze bust#Pioneer Square#Magnificent Mile#DuSable Museum#African American history

598 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1932, our beloved Dr. Carter G. Woodson wrote: "I have never wanted wealth. I do not know what would become of me if I have to spend twenty-five thousand dollars a year on myself. I would rather have an allowance of twelve and a half a week. The only need I have for money is to relieve the stress of others. It would take up too much of my valuable time to devise selfish schemes for throwing away a large fortune, and I would not have time to help humanity."

How do you live in a world that places value and importance of money? #TBT #CarterGWoodson #History #BlackHistory

(ASALH) Alt-text: Black and white image of Dr. Carter G. Woodson

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary McLeod Bethune, Nannie Helen Burroughs, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, and Mary Church Terrell, were just a few notable women with whom our beloved Dr. Carter G. Woodson was known to associate with. Part of the reason Dr. Woodson was so successful in his pursuit of preserving, disseminating, and institutionalizing Black History was due to the support of women, in particular Black women.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The oppressor has always indoctrinated the weak with his interpretation of the crimes of the strong..”

“Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history.“

“At this moment, then, the Negroes must begin to do the very thing which they have been taught that they cannot do.”- Dr. Carter G. Woodson

CARTER™️ Magazine carter-mag.com #wherehistoryandhiphopmeet #historyandhiphop365 #cartergwoodson #cartermagazine #carter #blackhistorymonth #blackhistory #history #staywoke

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#carter g woodson

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

National Parks Conservation Association: Celebrating the 'Book Man' of Washington, D.C. · National Parks Conservation Association

The pioneering educator Carter G. Woodson founded the precursor to Black History Month in 1926. Though temporarily closed for renovations, the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site is scheduled to reopen later this year.

Decades ago, residents of Washington D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood would regularly see a man walking down 9th Street carrying books in his arms — so many books, they were sometimes piled high enough to obscure his face. Thus, the groundbreaking historian Carter G. Woodson, known nationally as the “Father of Black History,” also earned himself the local nickname of “Book Man.”

It is a fitting tribute to a scholar who devoted his life to learning and education, who changed cultural awareness by documenting and distributing information on African American history and achievements, who wrote or coauthored more than 20 books — and who lived in a home filled with stacks and stacks of reading material.

Originally from Virginia, Woodson moved to Washington, D.C., to study at the Library of Congress while he was completing his doctoral degree at Harvard University. He purchased the 9th Street home in 1915 and lived there from 1922 until his death in 1950, keeping not just his extensive personal library on the premises, but also the offices of two grassroots organizations he founded and their numerous books and publications as well.

In 2001, after the home had stood vacant for years, the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed it on its list of America’s Most Endangered Historic Places. Congress designated the building as a national park site in 2006, as well as the buildings on either side of the main residence, but all three structures needed extensive stabilization and restoration work.

Carter G. Woodson site

Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site in Washington, D.C.

The Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site officially opened to the public in May 2017, then closed again for more extensive renovations. Fortunately, the home is scheduled to open again later this year.

When the home was reopened in 2017, it had very little in the way of furnishings or personal effects, and visitors weren’t able to see the Book Man’s actual books — many of which were donated to universities and other learning institutions decades ago. They were, however, able to get an authentic feel for how Woodson lived and worked.

The interior and exterior of the building were painstakingly renovated to resemble its appearance in Woodson’s time, including reconstructing the original façade brick by brick, rebuilding a circular staircase, and restoring original fireplaces and flooring.

Woodson, who was deeply professionally driven, reportedly joked that his property was not a home office, but an “office home.” Even empty, the house and rangers’ interpretation of it offer insight into Woodson’s strict character, his considerable professional accomplishments, and his connections to contemporaries he both taught and learned from, such as Mary McLeod Bethune, Nannie Helen Burroughs and Langston Hughes.

#Celebrating the 'Book Man' of Washington#D.C#Dr Carter G Woodson#Black History Month#Black History Matters#2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Rosalyn Marian Terborg-Penn (October 22, 1941 - December 25, 2018) pioneering scholar in African American Women’s History was born in Brooklyn to Jeanne Van Horn Terborg, a clerical worker, and Jacques Arnold Terborg, a jazz musician born in Suriname.

She attended Queens College, City University of New York, where she first became involved in the Civil Rights Movement as a charter member of the campus NAACP chapter. She protested its decision to prohibit Malcolm X from giving a speech there. She tutored African Americans in Prince Edward County, Virginia where schools had been closed following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision.

She earned a BA in History from Queens College. She joined “DC Students for Civil Rights,” lobbied for the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s passage, and worked at Friendship House, where she met her husband William Penn. She received an MA in US and Diplomatic History from GWU and began working at Morgan State University.

She published A Special Mission: The Story of Freedmen’s Hospital, 1862-1962. She earned a Ph.D. in African American history from Howard University. Her dissertation was titled “Afro-Americans in the Struggle for Woman Suffrage.” She was promoted to associate professor at Morgan State University and became its coordinator of history graduate programs. She developed the history Ph.D. program and was the director of the Oral History Project.

She co-founded and became the first national director of the Association of Black Women Historians. She became the first woman of color to chair the American Historical Association’s Committee on Women’s History.

She published over 40 articles and seven books, most notably African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850 to 1920. This work won the ABWH’s Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Prize. She received Towson University’s Distinguished Black Marylander award. She received the Association for the Study of African American Life and History’s Carter G. Woodson Scholar’s Medallion and Morgan State University’s Outstanding Woman Award. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #alphakappaalpha

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What You Need To Know About The Origins Of Black History Month

Black History Month is Considered one of the Nation’s Oldest Organized History Celebrations, and has been Recognized by U.S. Presidents for Decades Through Proclamations and Celebrations. Here is Some Information about the History of Black History Month.

— By Jesse J. Holland | February 1, 2024 | Associated Press

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. locks arms with his aides as he leads a march of several thousands to the court house in Montgomery, Alabama, March 17, 1965. From left: Rev. Ralph Abernathy, James Foreman, King, Jesse Douglas, Sr., and John Lewis (partially out of frame). (AP Photo)

How Did Black History Month Start?

It was Carter G. Woodson, a founder of the Association for the Study of African American History, who first came up with the idea of the celebration that became Black History Month. Woodson, the son of recently freed Virginia slaves, who went on to earn a Ph.D in history from Harvard, originally came up with the idea of Negro History Week to encourage Black Americans to become more interested in their own history and heritage. Woodson worried that Black children were not being taught about their ancestors’ achievements in American schools in the early 1900s.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” Woodson said.

Carter G. Woodson in an undated photograph. Woodson is a founder of the Association for the Study of African American History, who first came up with the idea of the celebration that became Black History Month. Woodson, the son of recently-freed Virginia slaves who went on to earn a Ph.D in history from Harvard, originally came up with the idea as Negro History Week to encourage black Americans to become more interested in their own history. (AP Photo)

Why is Black History Month in February?

Woodson chose February for Negro History Week because it had the birthdays of President Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Lincoln was born on Feb. 12, and Douglass, a former slave who did not know his exact birthday, celebrated his on Feb. 14.

Daryl Michael Scott, a Howard University history professor and former ASAAH president, said Woodson chose that week because Black Americans were already celebrating Lincoln’s and Douglass’s birthdays. With the help of Black newspapers, he promoted that week as a time to focus on African-American history as part of the celebrations that were already ongoing.

The first Negro History Week was announced in February 1926.

“This was a community effort spearheaded by Woodson that built on tradition, and built on Black institutional life and structures to create a new celebration that was a week long, and it took off like a rocket,” Scott said.

Why The Change From a Week To a Month?

Negro History Week was wildly successful, but Woodson felt it needed more.

Woodson’s original idea for Negro History Week was for it to be a time for student showcases of the African-American history they learned the rest of the year, not as the only week Black history would be discussed, Scott said. Woodson later advocated starting a Negro History Year, saying that during a school year “a subject that receives attention one week out of 36 will not mean much to anyone.”

Individually several places, including West Virginia in the 1940s and Chicago in the 1960s, expanded the celebration into Negro History Month. The civil rights and Black Power movement advocated for an official shift from Black History Week to Black History Month, Scott said, and, in 1976, on the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Negro History Week, the Association for the Study of African American History made the shift to Black History Month.

Six Catholic nuns, including Sister Mary Antona Ebo, front row fourth from left, lead a march in Selma, Ala., on March 10, 1965, in support of Black voting rights and in protest of the violence of Bloody Sunday when white state troopers brutally dispersed peaceful Black demonstrators. (AP Photo, File)

Presidential Recognition

Every president since Gerald R. Ford through Joe Biden has issued a statement honoring the spirit of Black History Month.

Ford first honored Black History Week in 1975, calling the recognition “most appropriate,” as the country developed “a healthy awareness on the part of all of us of achievements that have too long been obscured and unsung.” The next year, in 1976, Ford issued the first Black History Month commemoration, saying with the celebration “we can seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

President Jimmy Carter added in 1978 that the celebration “provides for all Americans a chance to rejoice and express pride in a heritage that adds so much to our way of life.” President Ronald Reagan said in 1981 that “understanding the history of Black Americans is a key to understanding the strength of our nation.”

— This Article by Former AP Reporter Jesse J. Holland was Originally Published on Feb. 2, 2017.

#Black History Month#Origins#Nation’s Oldest Organized History Celebrations#Dr. Martin Luther King#Montgomery | Alabama#Rev. Ralph Abernathy | James Foreman | Jesse Douglas Sr. | John Lewis#Negro History#Presidential Recognition

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,”- Dr. Carter G Woodson

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carter G. Woodson - Quote

We are closing out Black History Month with a quote from the Father of Black History Month, Dr. Carter G. Woodson. Click the link to learn more or listen via podcast. #BlackMaill4u #BlackHistoryMonth #BlackHistoryQuote #CarterGWoodson #BlackHistoryFact

Welcome To Black Mail! Where we bring you Black History, Special Delivery. We close out Black History Month with a quote from the Father of Black History Month, Dr. Carter G. Woodson. “We have a wonderful history behind us…and it is going to inspire us to greater achievements.” -Dr. Carter G. Woodson Dr. Woodson is so right! Our history is rich and wonderful, and it will propel present and…

View On WordPress

#African American History#Black History#Black History Fact#Black History Month#black history quotes#blackmail4u#Carter G. Woodson

14 notes

·

View notes